Sports Drinks, Skill Maintenance and Cricket Performance

Guest Article by Matthew Lees, BA

The topic of sugar consumption is a key aspect of the Mac-Nutrition philosophy, and there is a wealth of information available within this website supporting a lower carb, ‘real food’ approach to nutrition. For sedentary populations in particular, this should be regarded as the de facto attitude in terms of diet for optimum health. However, athletes often require bespoke modifications to this paradigm to achieve top performance. Carbohydrate supplementation in the form of sports drinks is regularly employed in a wide range of sporting activities, and whilst these beverages are pointless and likely harmful for sedentary individuals, they may be a valuable aid for athletes. The purpose of this article is to provide an insight into sports drinks and the circumstances that warrant their consumption.

Introduction

Sports drinks represent a rapidly expanding and lucrative industry, with a wide range of brands and manufacturers operating within a highly competitive market. Although each of these brands may claim to possess superior benefits over their rivals, most of them are formulated in a similar fashion. Typically, this formulation is geared towards the prevention of dehydration, the supply of carbohydrates and electrolytes, and also intended to be highly palatable (1). There has been a wealth of research conducted into the performance-enhancing properties of these beverages. It has been highlighted that for prolonged exercise in particular, a sports drink may delay the onset of fatigue and increase the amount of work performed in a given time (2). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that a soccer player may benefit from a sports drink in being able to cover a greater distance during a match, or being able to produce greater intensity for short bursts. However, it has also been suggested that there is no scientific evidence for the consumption of a sports drink with relation to exercise of less than 1 hour in duration (3). This is disputed, as carbohydrate intake has been shown to improve performance in exercise tasks lasting only 45 – 60 minutes, during which blood glucose levels do not fall and 5 – 15 grams of exogenous carbohydrates are oxidised (4). This particular study by Carter et al. (2005) found that sports drink consumption was beneficial for exhaustive cycling activity in a hot environment. In addition, research into the effects of a sports drink on high-intensity exercise of 1 hour in duration has demonstrated an improvement in performance when compared to a water placebo (5). With reference to this study, intermittent shuttle run activity of up to an hour in duration (such as during a football match) may benefit from the consumption of a sports drink.

It would seem then that there is some degree of conjecture regarding these beverages and their effects on performance. Professor Tim Noakes has emphasised the fact that the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has drawn up drinking guidelines that favourably promote the consumption of sports drinks over water for all who participate in activity. Also, the Gatorade Sports Science Institute is a platinum sponsor of the ACSM (3) and has sponsored numerous studies on sports drinks. There may be a conflict of interest where research sponsorships are involved, and sports drinks seem to be put forth as the panacea for improved sporting performance regardless of context.

Sports Drinks and Cognitive Performance

Glucose supplementation may be involved in the attenuation of a decline in motor skill execution. This is achieved through the maintenance of plasma glucose levels and the provision of substrates for the central nervous system. A paper on squash performance found that a 6.4% carbohydrate beverage provided improved visual reaction time over a water placebo (6), which gives some credibility to these assertions. However, the literature as a whole indicates mixed findings in this area and there is a lack of empirical evidence (knowledge gained from direct, scientific observation) that a sports drink can influence high-level cognitive performance, especially in team games.

In 2011 I conducted a study looking at cricket performance, due to the dearth of research in this area with reference to sports drinks and skill maintenance. The main focus of the study was pace bowling. The rationale for this was the association of Gatorade with cricket in Australia, and the potential benefits to performance alluded to in several research studies. The desire to examine the efficacy of a sports drink in terms of skill maintenance was also a key factor, as well as the physically demanding nature of the activity itself. I opted to measure bowling accuracy and the physiological markers of heart rate, perceived exertion, and blood glucose.

Dehydration is likely to negatively affect sporting performance and specifically fast bowling performance (7). Despite this, my research aimed to specifically research the provision of sugar, electrolytes and water (sports drink) versus water alone therefore dehydration would not be a confounder here. Is there really a need for fast bowlers to drink these sugary sports drinks, and is their association with top sporting organisations good for the general public? I set out to find an empirical answer the former; I’ll let you decide on the latter.

Experimental Method

The experimental protocol involved two trials separated by 7 days, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design. This is to say that each participant acted as their own control, and experienced both trial conditions.

The experimental protocol involved two trials separated by 7 days, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design. This is to say that each participant acted as their own control, and experienced both trial conditions.- The beverage formulation used was 6% glucose; 25 mg sodium/100mL whilst the placebo was water. Both beverages were flavoured with blackcurrant cordial. Fifteen minutes before the experiment, each participant was asked to drink 8 ml/kg/BM of either beverage at random.

- All food and drink consumed 24 hours before the trial session was documented.

- Each trial session consisted of a warm-up followed by bowling 6 overs (an over being 6 deliveries) as this is a typical spell in club cricket and concurs with the ECB Fast Bowling Guidelines for young players. In addition, the extension of the bowling spell beyond 6 – 8 overs has been known to cause a decline in speed and accuracy (8). Thus, a decline in accuracy due to other factors was minimised, meaning that any effects of the beverages on accuracy could be attributed to the central nervous system and not muscular fatigue.

- The accuracy of bowlers for each delivery was objectively measured using a bespoke targeting sheet (pictured). The sheet denotes three scoring areas, with the 100-point zone acting as a set of stumps, with the same dimensions.

- Heart rate and RPE data were obtained throughout the protocol, whilst serum glucose was measured immediately before and after the 6 over spell.

Research Findings

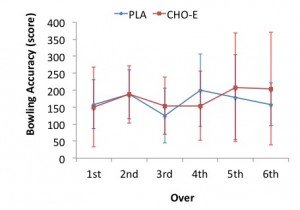

The findings of the research indicated no significant differences in bowling accuracy after consuming either beverage (the graph below denotes the mean total scores for each beverage group across the 6 over period). Furthermore, the consumption of a sports drink induced significantly higher mean pre-test resting heart rates than those shown in the placebo group (placebo: 90.7 ± 8.5 beats·min-1; sports drink: 101.5 ± 8.7 beats·min-1; p = 0.04). However, the post-test resting heart rates were both similar. It may be speculated that this may be part of a delivery system for glucose to the central nervous system (9), but there is a lack of consistent sport-specific research findings in the literature to support this. The ratings of perceived exertion remained similar in both groups save for immediately after the third over, during which a decrease in RPE was observed in the sports drink group. This decrease was isolated, and although a trend developed following the third over this was non-significant. Blood glucose was significantly higher prior to bowling in the sports drink group, suggesting that glucose had been rapidly absorbed by the GI tract (placebo: 4.13 ± 0.83 mmol·l-1; sports drink: 6.29 ± 1.42 mmol·l-1; p = 0.028). This concentration had declined after 6 overs but the glucose level in the placebo group had remained similar to the pre-test measurement. This may be a result of gluconeogenesis (production of new glucose), whereby the glucose required was “manufactured” from other substrates to maintain serum glucose levels. In the sports drink group, it is probable that the decline in blood glucose over the 6 over period was due to a hyperinsulinemia response (5). That is, as the serum glucose concentration increased a corresponding bolus of insulin was released to bring it back down.

Practical Implications

It  can be suggested that there is a lack of a rationale for the ingestion of a sports drink prior to commencing a bowling spell in cricket, and there were no beneficial effects with regards to skill maintenance based upon these findings. This concurs with the majority of existing literature in this area. In addition, it reinforces the notion that there is simply no need for sports drink consumption during high-intensity, short-duration sporting activities (~40 minutes in this case). The widespread dogma concerning the consumption of a sports drink before, during, and after any kind of athletic endeavour is fantastic for the manufacturers of these beverages, but poses several physiological consequences. Professor Robert H. Lustig has been extremely vocal about the levels of fructose in commercial beverages, and he has cited the fact that the primary consumers of sports drinks are typically sedentary individuals. This is evident from his YouTube presentation entitled ‘Sugar: The Bitter Truth’. The beverage formulation used in this study was made from scratch and thus no brand names were used, therefore it lacked the additives of commercial drinks. It also used dextrose powder as the carbohydrate source and not glucose-fructose syrup or high-fructose corn syrup.

can be suggested that there is a lack of a rationale for the ingestion of a sports drink prior to commencing a bowling spell in cricket, and there were no beneficial effects with regards to skill maintenance based upon these findings. This concurs with the majority of existing literature in this area. In addition, it reinforces the notion that there is simply no need for sports drink consumption during high-intensity, short-duration sporting activities (~40 minutes in this case). The widespread dogma concerning the consumption of a sports drink before, during, and after any kind of athletic endeavour is fantastic for the manufacturers of these beverages, but poses several physiological consequences. Professor Robert H. Lustig has been extremely vocal about the levels of fructose in commercial beverages, and he has cited the fact that the primary consumers of sports drinks are typically sedentary individuals. This is evident from his YouTube presentation entitled ‘Sugar: The Bitter Truth’. The beverage formulation used in this study was made from scratch and thus no brand names were used, therefore it lacked the additives of commercial drinks. It also used dextrose powder as the carbohydrate source and not glucose-fructose syrup or high-fructose corn syrup.

This particular study has illustrated an increase in blood glucose concentration and heart rate prior to activity after consuming sports drinks, without any beneficial effects on skill performance or perceived exertion. The same effects can be obtained by consuming water before commencing a bowling spell, and this is the key message to be taken from this article. As a side note, it is interesting that milk has been described as a more nutrient dense beverage when compared to traditional sports drinks (10). This has practical implications concerning individuals who partake in strength and endurance activities but also sports scenarios. In addition, milk has been shown to be a more effective post-exercise rehydration drink than sports drinks or water (11). Despite this empirical evidence, I cannot see Cricket Australia forming a partnership with Dairy Australia in the immediate future.

To conclude, I would recommend that water be consumed before cricketing activities as well as short, high-intensity activities of a similar nature (such as baseball). A key message from this research is the specificity it has with relation to actual match conditions. A considerable amount of research on sports drinks has been conducted in labs that has relatively little crossover to the sports field, and this study accounted for the fact that bowlers cannot take on board sufficient fluids between overs. Despite the results of this study, there is still a need for greater enquiry with regards to sports drinks and skill maintenance in other sporting areas. In addition, the formulation and dosage protocol of such research may be key areas to focus on. It is clear in my opinion that sports drinks are not the panacea they are often made out to be by manufacturers and corporate interests; however they do have their uses in the correct situations, such as long-duration endurance events or competitive intermittent sprint sports.

References

(1) Coombes, J.S., and Hamilton, K.L. (2000). The Effectiveness of Commercially Available Sports Drinks. Sports Medicine, 29(3): 181-209

(2) Hill, R.J., Bluck, L.J.C., and Davies, P.S.W. (2008). The hydration ability of three commercially available sports drinks and water. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 11(2): 116-123

(3) Noakes, T.D. (2007). Drinking guidelines for exercise: What evidence is there that athletes should drink “as much as tolerable”, “to replace the weight lost during exercise”, or “ad libitum”? Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(7): 781-796

(4) Carter, J., Jeukendrup, A.E., and Jones, D.A. (2005). The effect of sweetness on the efficacy of carbohydrate consumption in the heat. Can J Appl Physiol, 30(4): 379-391

(5) Davison, G.W., McClean, C., Brown, J., Madigan, S., Gamble, D., Trinick, T., and Duly, E. (2008). The Effects of Ingesting a Carbohydrate-Electrolyte Beverage 15 Minutes Prior to High-Intensity Exercise Performance. Research in Sports Medicine, 16(3):155-166

(6) Bottoms, L.M., Hunter, A.M., and Galloway, S.D.R. (2006). Effects of carbohydrate ingestion on skill maintenance in squash players. European Journal of Sport Science, 6(3): 187-195

(7) Devlin, L.H., Fraser, S.F., Barras, N.S., and Hawley, J.A. (2001). Moderate levels of hypohydration impairs bowling accuracy but not bowling velocity in skilled cricket players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 4(2): 179-187

(8) Noakes, T.D., and Durandt, J.J. (2000). Physiological requirements of cricket. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(7): 781-796

(9) Kennedy, D.O., and Scholey, A.B. (2000). Glucose administration, heart rate, and cognitive performance: effects of increasing mental effort. Psychopharmacology, 149: 63-71

(10) Roy, B.D. (2008). Milk: the new sports drink? A Review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr, 5(15): 1550-2783

(11) Shirreffs, S.M., Watson, P., and Maughan, R.J. (2007). Milk as an effective post-exercise rehydration drink. Br J Nutr, 98(1): 173-180

Matt Lees is a Sport Scientist with a degree in Sport and Exercise from the University of Derby and is currently working towards his Masters in Sport and Exercise Nutrition at Leeds Metropolitan University. Matt's passions lie in both sport specific training and nutrition as well as dietary adaptations for long-term health. Alongside his studies, Matt has worked in the areas of performance analysis at county cricket club level as well as completing an internship in exercise physiology gaining valuable experience of laboratory testing and research.

Matt presented these research findings at the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences (BASES) Student Conference.